Bruno Maçães is following the Ukrainian crisis first-hand. During his stay in Kiev, we reached out to him remotely to discuss the latest developments and possible outcomes. Maçães has no doubt that Russia can't live next to a strong Ukrainian state. In his own words: "Russia essentially wants to destroy or dramatically weaken the Ukrainian state. It is that simple." Here is the interview with the author, senior fellow at the Hudson Institute and former Portuguese secretary of state for European affairs.

The last time we spoke together, you were in Kabul. Now, six months later, you are in Kyiv, another place on the brink of the conflict. What's the situation on the ground?

Well, it is pretty surreal because you have these announcements of an imminent war all the time, like 24/7. They are coming here from every international media, starting with CNN and finishing with Le Monde, and they come every day for the last three or four days, announcing that the war is about to begin. But only people reading them and watching them are foreign journalists, nobody else.

Journalists?

Yes, journalists. Local people continue to live very normally, and they don't care much. But journalists! I have never seen a city so covered with journalists. They bump into each other; they interview each other or interview some lost tourists or expats who stay. There are hundreds and hundreds of them because it is so easy to get here. Air routes and airlines are running fine, no problem on the ground, so why not come to enjoy a little bit of adrenaline and bring it to folks back home. So I have seen people from all over the world, there are journalists from Sri Lanka, there are journalists even from New Zealand...

How about ordinary Ukrainians?

Ukrainians themselves are pretty calm. It is very tense for them, no doubt, but this is what has been going on for eight years. So, either you go mad, or emigrate, or you must go on with life. And most Ukrainians opt for the third option. And to survive this is to learn how to react normally. Let me tell you a story from yesterday. I was sitting at a café and was following the news. The café was full, packed. At that exact moment, Anthony Blinken went live on TV and briefed the UN Security Council about some urgent intelligence that war is indeed about to begin. So, I was following his story with anxiety, of course. That was the US Secretary of State telling us that war is coming on the city where I was! But when I looked around, I found out I was the only one watching the news—nobody else. Every Ukrainian around me was chatting and laughing and eating desserts. They were not concerned whatsoever. That was remarkable, really remarkable.

Could you elaborate more on this?

You know you are in a country under siege by one of the largest armies in the world. For them, the Russian army, moving and running through the borders, might be a matter of minutes. And here I am talking not only about the air attacks and missiles. Their troops are half an hour from the second largest city of Kharkiv. And people are still calm. Brave. And let's be honest about one thing: If a situation like this, so escalated, so dangerous, would happen (somewhere else) in Europe… I believe that many European countries would now be breaking apart. There would be a state of emergency; there would be almost a police state. But not here. As a foreigner, you walk around the city, and nobody wants to see your passport or your ID. I have been here for a week now, but nobody has asked. Not a single time. Can you believe this?

What is the outlook for the future?

There will be more urgency of some kind for sure. But now you feel free here, relaxed. Restaurants are magnificent and full of people; dance clubs are open every night. Some people might say cynically that this is the orchestra on the Titanic before the collapse and sinking. But I don't think so, and I wouldn't say I like that. On the contrary, this country is prepared to live like this for decades and has the right approach to manage it.

How?

To continue with life and save your energies for a very prolonged conflict.

In just six months, Ukraine is the second geopolitical clash you have the opportunity to see literally from the ground. Could you compare the current Ukraine escalation with your experience in Afghanistan six months ago?

Ukraine is a bigger game, and it is more complicated than Afghanistan. But there is one commonality, which is the retreat of American power. We could have seen this multiple times during the last years in different parts of the world; instability came whenever American power left. And then local actor hurries in to fill the void. It was the Taliban in Afghanistan, and it was Russia in Ukraine. Different geographies, but same dynamic.

You mentioned that the dynamics are the same. How is it probable to reach some form of compromise and détente?

That is where I see the most significant difference. There was a straightforward agreement between the US and the Taliban. Many people were offended by that agreement, yes. Their sensibilities were offended. But the conclusion itself was fast and easy. In Ukraine, it is much more complicated because stakes are higher, and Ukraine is no Afghanistan. Ukraine is a big country with 40 million people who have their own views and firm opinions about their history, present, and future. I honestly think that if Ukraine didn't have these strong views, we would have already seen some accommodation between the US and Russia. Détente that you mentioned. But Ukraine doesn't want any Munich.

Munich agreement analogies have been something we have heard in the media multiple times in recent days...

This is the point where the country is stubborn. Also, it is not entirely dependent and fully aligned with the American views. Ukraine regards the US as an ally, but still, it keeps its world views and can express a strong disagreement with the US. And Washington shouldn't be surprised because this stubbornness in strategic thinking is in the best traditions of the Soviet Union. And believe me, Ukrainian national tradition is much longer than the Soviet Union, but its strength is similar.

What does Ukraine want?

Ukraine wants to decide its destiny. Ukrainians and Ukrainian elites, political and economic, are very independent-minded. They believe that it's their country and nobody else's, and they want it to be independent and want to shape its future.

Let's zoom out a little bit and look at the whole situation from the perspective of a chess. We see four players with their four grand strategies. On one side, there is the United States, supported by the UK. On the other side, there are Russians. And then, Ukraine is in the middle. Finally, we see continental Europe on the chessboard, led by Germany and France but divided between Western Europe and the CEE. Could you elaborate on how you see the strategies of these chess players?

Well, yes, it resembles a grand heavy chessboard. Kings, queens, bishops, and pawns!

Maybe let's start with Russia.

The Russian situation is evident to me. Russia essentially wants to destroy or dramatically weaken the Ukrainian state. It is that simple. Perhaps Ukraine might be allowed to remain nominally, formally an independent state, but what Russia cooks for Ukraine, in reality, is to become a failed state essentially. A weak state and weak country that Russia can have control over. Not just politically but also economically, where Russian business interests would be present and dominant. Then, Ukraine would be part of the Russian world again, not just through a sphere of influence but an integral part of the Russian world next to Belarus.

What kind of tactics do you see?

Anything can be used – economic pressure, a political one, and information warfare. Even legal instruments like the Minsk agreements are being used to transform the strong to weak state. I think Russia can't live next to a strong Ukrainian state, which might become aligned with the West, or at least to become close to the West. That would be an unacceptable scenario for Russia and Vladimir Putin.

If we go with our chess analogy a little further on, then on the other side of the board, we see chess pieces waving American and UK flags.

Their thinking is very similar to Putin but opposite. They ask themselves: do we accept that Ukraine will become part of the Russian world again? That's the central theme and question, which different people answer differently. Some of them might be tempted to create some form of détente, with a demarcation line in the middle. They feel that if you draw the border between the West and Russia on the western borders of Ukraine, it will be a sustainable solution long term. They can also say that Ukraine has never been part of the western civilization. But even these people in Washington and London are still afraid of one thing...

...which is?

I think that the majority of the elite in the UK and US are very suspicious that if Ukraine becomes part of the Russian world, Russia will not stop there. That it will just move its appetite further to the West. They are afraid of it. Plus, there is a problem with central Europe. I don't think it would be comfortable for central Europe to have Russia effectively on Slovak, Polish, and Hungarian borders.

And because of these two points, the minimum that the US and UK would accept is the idea of Belarus and Ukraine as a buffer or neutral states. That's the minimum. Some dream about the maximum to expand the Western world to Ukraine, and potentially one day – maybe to Russia itself.

Would finlandization be acceptable to Russia?

I don't think Russia would accept a neutral Ukraine, no. A journalist from Switzerland asked me the other day whether some form of Swiss–EU cohabitation might not be a solution.

How shall I understand it?

That Ukraine would be part of the European world in economics and cultural spheres, but in national security and military, it will stay completely neutral. But I don't think Russia would accept it. Moscow has already shown that it detests the economic and cultural independence of Ukraine also. Let's not forget that the main question on the table eight years ago was not Ukraine membership in NATO, but its application to become a part of the European Economic Area. It was about trade and economy, not about security. And we all know how it ended.

And thus, you have forty million Ukrainians stuck between the two superpowers.

Yes. They are in the middle but still want to preserve their independence. Plus Ukraine has become much closer to the Western world and is still drifting further from Russia. For me, this radical transformation of Ukraine is one of the incredible transformations of the modern era. Just a decade or two ago, Ukraine was effectively part of the Russian world one hundred percent, and now the mentality shifted exceptionally quickly. Now, most Ukrainians, particularly young ones, don't look up to Russia. They look to Europe. That's where they go for holidays, and Europe is what they want to be part of. Still, they always want to be independent and not follow instructions or imitate any other country. But in its heart, Ukraine regards itself as being European.

What are the sources of inspiration? To where they are going for supporting arguments? To history?

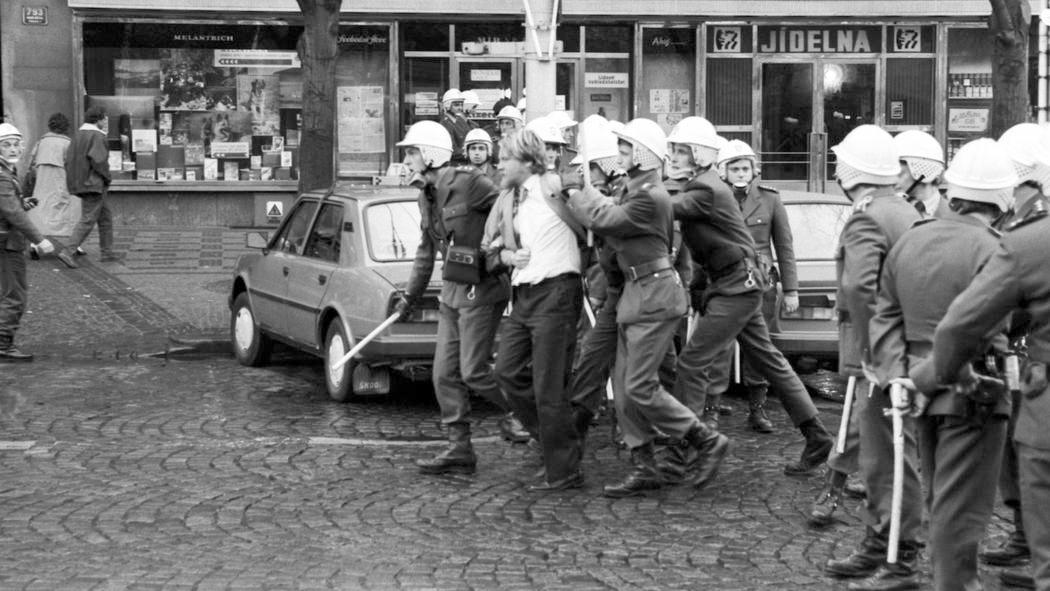

Actually, yes, that's exactly what is happening. There is a lot of effort by Ukrainian intellectuals to go back into the past and find a distinctively Ukrainian tradition separate from Russia. The tradition that is more democratic and connected to free-spirited Cossacks. From this perspective, they understand Ukraine as a border zone between the two worlds, which brings a spirit of freedom. It is very similar to the ethos of the West in the history of the United States: free people in a free land. By the way, we shall remember that the Soviet Union became a federation, a union of republics, because of Ukraine. So, Ukraine was always a reasonable limit on Moscow's power, sort of checks and balances. And what we see now is Ukraine recovering this idea that power shall be limited. And at the same time, it might be that Russia is becoming more authoritarian and centralized, precisely because Ukraine is no longer part of its political system.

What is the position of France and Germany?

France and Germany are clearly on the side in the West; there is no doubt about that. But it is the West that would be more than willing to try to reach an accommodation with Russia and more inclined to believe that it's possible to have a very stable delimitation of areas.

How would that work practically?

Especially in Germany, many people believe that such delimitation would make Russia happy and, therefore, the European Union would be able to coexist with newly content Moscow. I suspect this phenomenon is influential in Germany because Berlin can't adopt any other course of action but accommodation. They don't have the military ability to do anything else. In a perfect world where it would be possible to reach an accommodation with Russia, both Europe and the US would agree to do that. But many people are skeptical, especially in the US, because what if that accommodation won't work and Russia will start trouble even within the EU or in the Balkans?

The US military is now moving again into Central Europe. Is it the start of a new interest of Washington in the region?

Yes and no. If something happens, I think that the US will have to step in once again. But they don't like that. You know: if accommodation turns out not to be stable, it becomes once again an American problem, and American want to turn to Asia, to China. That's also part of the issue here that cannot be solved quickly. Americans want to be somewhere else, Europeans are weak, and Russia is bellicose.

What might be the next moves on the chessboard?

I don't think that Russia's current push will create a stable future. At the same time, nobody else has an arrangement that would be stable for this part of the world. Therefore, everyone is just looking forward and waiting for the moves of others. But this is where I'm not as pessimistic as most people. Because I see a willingness of everyone to pause, analyze and look for any arrangement—even the short-term one. And more importantly, I don't see anyone who thinks that war will create long-term understanding. I don't see anyone in Europe, not the US or Russia.

Not even in Russia?

Not even in Russia, I would dare say. They don't seem to think that war is the way to reach their long-term arrangement. Militarized diplomacy, yes, but not full-scale war.

Thank you, Bruno, for your comments as always, and let's see what upcoming days and weeks will bring us. Safe travels in the meantime. Godspeed!

Bruno Maçães, PhD

Bruno is a senior fellow at Hudson Institute and a senior advisor at Flint Global in London. He is former Secretary of State for European affairs (from 2013 to 2015) and was decorated by Spain and Romania for his services to the government.

Dr. Maçães received his doctorate in political science from Harvard University in 2006. His dissertation was awarded the Richard Herrnstein prize for the best dissertation in the social sciences. He has taught at Yonsei University in Seoul, Bard College in Berlin, and Renmin University in Beijing. In 2008 he was a research fellow at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, DC, where his work focused on the political implications of the biotechnological revolution. He is the author of several books on international affairs, including The Dawn of Eurasia, Belt and Road and History has Begun.

Bruno is a regular commentator on the international media and has written for the Financial Times, Politico, The Guardian, and Foreign Affairs.

PhDr. Jan Ruzicka, MBA

Jan is a Chief External Affairs Officer at the Home Credit Group, the world’s leading consumer finance provider. Based out of Hong Kong, Jan runs company networks in the US, Asia and Europe. Before that, he used to live in Beijing, Cambridge and Prague. He even spent ten years working for the Czech Government, advocating and shaping health reform as the Director-General at the Ministry of Health.

Jan teaches Behavioural Economy and the Disruption of Finance and Healthcare at universities in Asia and Europe. He is especially interested in how innovation can create financial inclusion and health equality.